Module 05

Digital Histories

XR as historiography and the digital landscape around Hashima

Overview

- Extended reality (VR, AR, immersive environments) is not a neutral window onto history — it is a form of historical argument

- Material authenticity (accurate objects and spaces) can coexist with social and interpretive failure

- The existing digital landscape around Hashima reveals a consistent pattern: visual sophistication combined with interpretive silence about contested histories

- Mechanics — the rules governing what users can do — make historical claims as powerfully as visual content

This module addresses how digital media — VR, AR, games, and immersive reconstructions — function as forms of historical argument. It then surveys the existing digital landscape around Hashima, revealing patterns of visual sophistication combined with interpretive silence.

Part One: XR as Historiography

Immersive reconstruction as historical argument

Extended reality — VR, AR, and immersive digital environments — is often presented as a technology of access: a way to visit places you cannot physically reach, to see things as they once were, to experience the past. But XR is not a neutral window onto history. It is a form of historical argument. Every reconstruction makes claims about what matters, whose perspective counts, and what the past means.

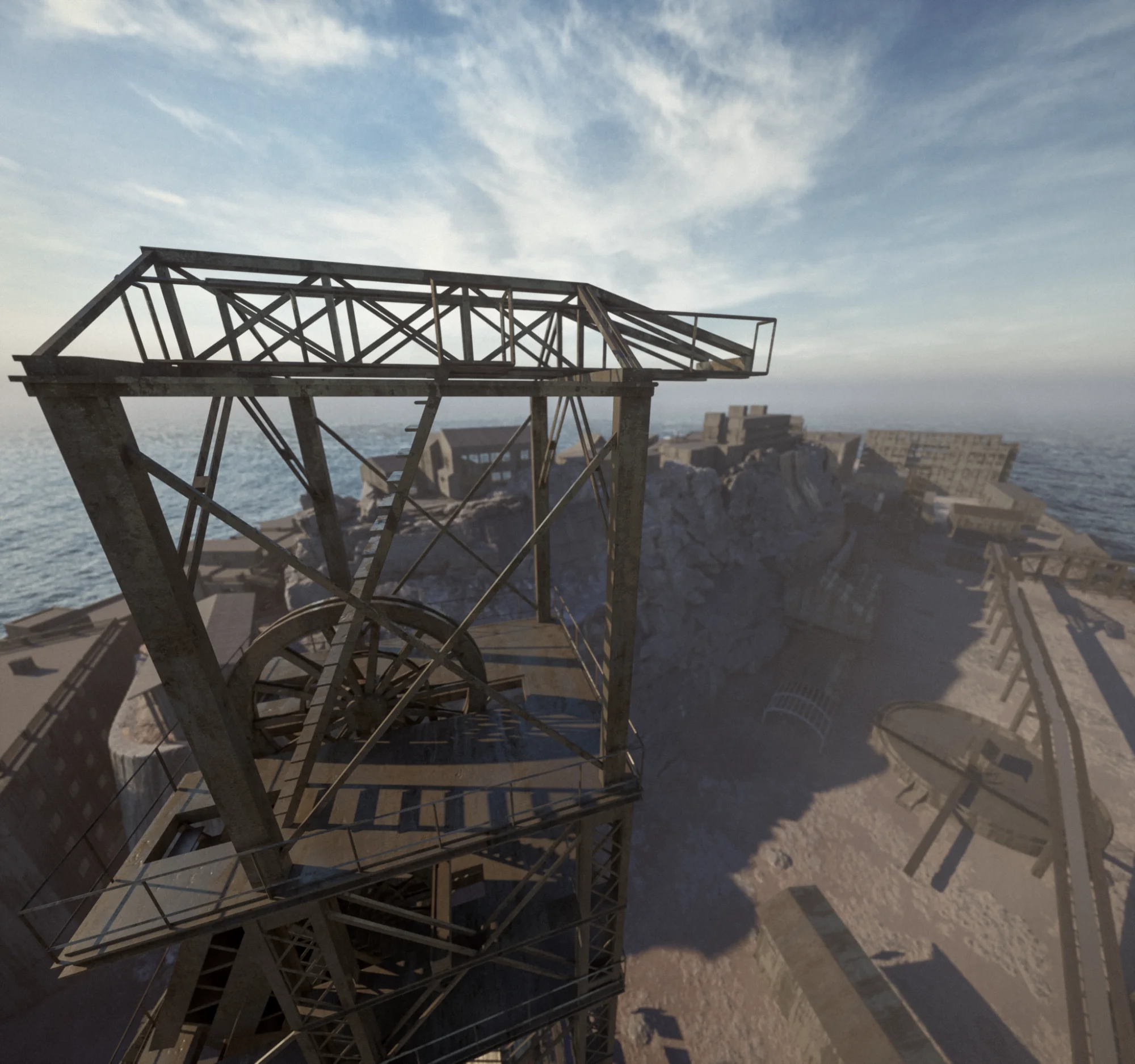

HashimaXR Prototype

Reconstruction showing apartment blocks and mine infrastructure from the early 1970s.

Reconstruction Is Argument

A digital reconstruction of Hashima in the 1970s involves thousands of decisions: which buildings to model, how to light the scene, what objects to place in apartments, what sounds to include, where the user can and cannot go. Each decision shapes interpretation.

Consider a simple example: an apartment interior. The designer chooses furniture, arranges objects, sets a time of day. The result feels "authentic" — it looks like a real space from the period. But authenticity to what? To the material culture of the era? To the experience of a particular resident? To the tourist imaginary of mid-century Japan?

Now consider what is not shown. Are there objects that indicate the occupant's ethnicity or origin? Is there evidence of the company-town structure that governed life on the island? Are there traces of the mine — the dust, the fatigue, the injuries? Is there any indication that, decades earlier, Korean and Chinese workers lived in segregated, inferior housing on the same island?

The reconstruction makes claims through inclusion and exclusion, through what it renders visible and what it leaves out. These claims may be implicit — the designer may not have consciously intended them — but they are claims nonetheless.

Material Authenticity vs. Interpretive Accountability

Heritage scholars distinguish between different layers of authenticity:

- Material authenticity: accurate reconstruction of objects, spaces, and surfaces

- Social authenticity: representation of social relations, practices, and identities

- Experiential authenticity: whether the experience as a whole supports historically informed understanding

Material authenticity in the HashimaXR prototype: detailed reconstruction of industrial infrastructure.

A reconstruction can achieve impressive material authenticity — getting the architecture right, the furniture period-appropriate, the lighting realistic — while failing at social and experiential authenticity. It can simulate the look of a place without representing the labor relations, power structures, or contested histories that shaped life there.

This distinction matters because material authenticity is often what institutions demand and what audiences perceive. A visually convincing reconstruction feels "real." It creates what researchers call a "sense of place" — an emotional and cognitive connection to a location. But if the reconstruction omits key aspects of a site's history, it produces a partial or distorted sense of place.

Interpretive accountability asks something different: not "does this look right?" but "does this represent the historical relations that structured life here, including the difficult ones?"

The Power of Immersion

Immersive media differs from films, books, or museum panels because it situates the user within the scene. You do not watch a representation of Hashima; you move through it. This has implications for how historical claims register.

Researchers distinguish between intravirtual effects (what happens within the simulation) and extravirtual effects (what happens to real people and institutions as a result of the simulation). Even if the events depicted are virtual, their effects on historical understanding, public memory, and real communities are entirely real.

The reconstruction's atmospheric rendering creates a powerful sense of place — but what histories remain invisible?

A VR experience of Hashima that reproduces the island's architecture while omitting coerced labor may leave users with the impression that they have encountered the site's complete history. The visual realism makes the interpretive gaps harder to perceive. Users do not see what is missing because the simulation feels comprehensive.

This is what makes omission in immersive contexts ethically significant. Withholding key aspects of a site's history, while presenting an experience as authentic, undermines users' capacity for informed historical judgment.

Mechanics as Historical Claims

In interactive media, mechanics — the rules that govern what users can do — are themselves a form of argument. A game or XR experience makes claims not only through what it shows but through what it allows.

Consider the difference between:

- An experience where you can go anywhere vs. one where certain areas are blocked

- An experience where information is freely available vs. one where you must search for fragments

- An experience where all voices are equally accessible vs. one where some testimonies are harder to find

- An experience that ends with resolution vs. one that leaves questions unanswered

Each of these design choices makes a historiographical claim. Blocking access to certain areas can simulate the experience of restricted knowledge or enforced silence. Requiring users to piece together fragments can model the difficulty of recovering marginalized histories.

HashimaXR's design documents describe mechanics intended to make silence and constraint legible to users. Moments when voices trailed off, when certain questions remained unanswered, when physical spaces were present but their histories inaccessible — these were not failures of content but deliberate attempts to represent the politics of historical omission within the experience itself.

Authenticity as Gatekeeping

The historian Esther Wright argues that terms like "historical accuracy" and "historical authenticity" often function as gatekeeping mechanisms. Different stakeholders invoke these terms to evaluate — and control — how the past is represented, but the terms mask underlying power dynamics.

The critical question, Wright insists, is not whether a representation is "accurate" in some objective sense but rather: whose accuracy? Accuracy to which version of events? Who gets to decide?

In contested heritage contexts, disputes over accuracy frequently stand in for deeper conflicts over responsibility and justice. Institutions can reject representations by calling them "inaccurate," "unbalanced," or "inappropriate" without explicitly defending historical erasure. The vocabulary of authenticity provides cover for political judgments.

Part Two: The Digital Ecosystem

Hashima in virtual space: a comparative survey

This section surveys the digital landscape around Hashima — the VR experiences, photogrammetric archives, games, and interactive installations that present the island to audiences who may never visit in person. Each project represents technological achievement. Each also makes historiographical choices about what to show and what to omit.

A Taxonomy of Digital Hashima

Digital representations of Hashima fall into several categories, distinguished by technology, institutional backing, and interpretive approach:

Museum Installations and Official Projects

Location-based experiences tied to institutional heritage interpretation:

- Gunkanjima Digital Museum — Located in Nagasaki, offers multiple XR experiences including HoloLens experiences and walking tour guides. Reconstructs mine shaft environment with impressive visual fidelity. Does not identify who labored there under coercive conditions.

- Sony Spatial Reality Display: Digital BOX Gunkanjima — Glasses-free 3D installation using photogrammetry, part of the Gunkanjima Museum VR Multilingual Interpretation Project. Emphasizes technological innovation and visual spectacle.

- Nagasaki City VR/CG Animations — Official VR and CG animations of Hashima Coal Mine and Takashima Hokkeikō, published by Nagasaki City's World Heritage Office in March 2025.

Gaming Platforms and Interactive Experiences

Projects distributed through gaming platforms, reaching younger and broader audiences:

- Fortnite: Gunkanjima Archive (Map Code: 4058-6239-4733) — A permanent Fortnite stage created by Heritage Databank using professional photogrammetry. Launched to commemorate the tenth anniversary of UNESCO World Heritage inscription. Features multiplayer and "hide-and-seek" gameplay modes. Frames the island as an "archive" but archives only visual data, not historical context regarding coerced labor.

- Visiting Battleship Island: A Photographer's Chronicle (Steam, 2024) — Walking simulator by XYimage emphasizing atmospheric exploration and photography. The ruin aesthetic dominates; colonial labor history is absent.

- GunkanjimaVerse (VRChat) — Public VRChat world created by VoxelKei, allowing social VR exploration of a reconstructed Hashima environment.

Documentation Projects

Projects that aim to preserve visual records of the island's current state or historical appearance:

- Google Street View / Arts & Culture (2013) — The first major digital documentation effort, using Google Trekker technology to capture the island's ruins. Framed as exploration of an "abandoned" site, with no reference to wartime labor.

- Heritage Databank — High-resolution 3D scanning for preservation purposes, used as source material for the Fortnite stage and other projects. Positions itself as heritage preservation while serving primarily as visual asset creation.

Common Patterns

Across this ecosystem, several patterns recur:

Thick Presence Plus Thin Narration

Each project achieves impressive visual fidelity. Photogrammetry captures surface detail with sub-millimeter accuracy. VR environments create compelling "sense of place." But this visual sophistication coexists with what the Japan-Korea Citizens' Guidebook diagnosed as "thin description": timeline-style narrative that reads as history while refusing causal, social, and juridical specification.

The result is thick presence plus thin narration — viewers receive a precise experience of space but only a thin account of the labor, coercion, and empire that structured that space. This is precisely the imbalance that UNESCO's 2021 decision criticized in physical heritage interpretation, now replicated in digital form.

The Ruin Aesthetic

Most projects emphasize decay, abandonment, and atmospheric emptiness. This aesthetic choice — presenting Hashima as a beautiful ruin rather than a former site of labor — forecloses questions about who worked there and under what conditions. The sublime experience of contemplating industrial modernity's impermanence displaces engagement with the human costs of that modernity.

Institutional Alignment

Projects with official endorsement or partnership — the Digital Museum, Sony's installation, the Heritage Databank archive — systematically avoid content that might conflict with authorized heritage narratives. Projects without institutional ties (such as HashimaXR) faced obstruction when they attempted critical interpretation.

Gamification as Heritage Outreach

The deployment of Hashima in Fortnite and VRChat represents a new frontier in heritage communication — reaching audiences who would never visit a museum or read a heritage brochure. Yet the gamification strips the site of historical context entirely. Players engage with Hashima as a visually interesting environment for multiplayer games, not as a site of contested memory.

What UNESCO Demanded

The 2021 UNESCO World Heritage Committee decision expressed "strong regret" that Japan had not implemented interpretive measures to present the "full history" of the Meiji Industrial Revolution sites. The decision specifically called for:

- Recognition that "a large number of Koreans and others" were "brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions"

- Interpretive strategies that "allow an understanding of the full history of each site"

- Displays that could be said to "memorialize the victims"

None of the digital projects surveyed here meet these requirements. The digital ecosystem around Hashima replicates, in virtual form, the same interpretive failures that UNESCO criticized in physical heritage interpretation.

Comparative Example: Hibakusha VR

Not all XR projects addressing difficult history in Nagasaki follow this pattern. NHK's Hibakusha VR projects use immersive media to document atomic bomb survivor testimony, centering victim perspectives and explicitly engaging with historical trauma.

The contrast is instructive. Institutional support for XR addressing atomic bomb memory has been substantial. Institutional support for XR addressing colonial labor memory has been conditional at best, obstructive at worst. The difference reflects not technological constraints but political choices about which difficult histories receive interpretive resources.

What HashimaXR Attempted

HashimaXR was designed to occupy a different position in this ecosystem:

- Reconstruct the island as a living community, not a ruin

- Center everyday life while making space for coerced labor histories

- Use a "two-voice" narrative system that juxtaposed different perspectives and periods

- Build an in-game archive of documents, testimonies, and images that users would assemble through exploration

- Design moments of silence, interruption, and incompleteness as historiographical interventions

This was XR as critical heritage practice — an attempt to use immersive media not for celebratory reconstruction but for engagement with contested, uncomfortable history.

This positioning threatened authorized narratives not by arguing against them directly but by demonstrating that alternative approaches were possible. The next module teaches you how to read the institutional positions that shaped this landscape.

Key Takeaways

- XR is historiography. Every reconstruction makes claims about what matters and whose perspective counts.

- Material authenticity differs from interpretive accountability. A reconstruction can look right while omitting key histories.

- Existing Hashima projects share common patterns. Thick visual presence combined with thin historical narration.

- The digital ecosystem replicates physical heritage failures. None of the surveyed projects meet UNESCO's "full history" requirements.

- HashimaXR attempted a different approach. Critical heritage practice using immersive media for engagement with contested history.

📝 Cite This Module

Gerteis, Christopher. "Module 05: Digital Histories." HashimaXR Learning Resource. SOAS University of London, 2025–2026. https://hashimaxr.netlify.app/learn/module-05/.

For other formats, see How to Cite · Full Bibliography